After walking around the building, sitting by the waterfall up the hill behind it, and strolling through the town, I went back in to see the Graciela Iturbide exhibition that was up. Apart from my desire to travel outside of Oaxaca to find quiet places, this show was a major reason to come to San Agustín. Iturbide is a photographer I’ve known about for some time, but without knowing much more than her famous photographs, like Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas, Juchitán , 1979.

The exhibition as a whole did not offer the kind of in-depth exploration of her work that I had hoped it might provide. Or, rather, it displayed a wide range of her work, but without any guidance about how it might be grasped. I didn’t take a photo that really shows the installation, but even from the image above you can maybe see that there were no labels on the walls. This meant that images from all across Iturbide’s career were put together without any indication of what year they were taken, let alone the title of the photograph. I’d be very curious to know how this decision was made. Does Iturbide want visitors to interact with her work as a series of formal images, floating (as it were) in a space without any context? It’s an odd choice, though I could say it did have the merit of forcing certain questions about her work to present themselves very directly.

For example: what was her relationship to Manuel Álvarez Bravo? I gather that she was his assistant, but I’d be curious to know more about their dialogue. Here, she’s clearly putting one over on him .

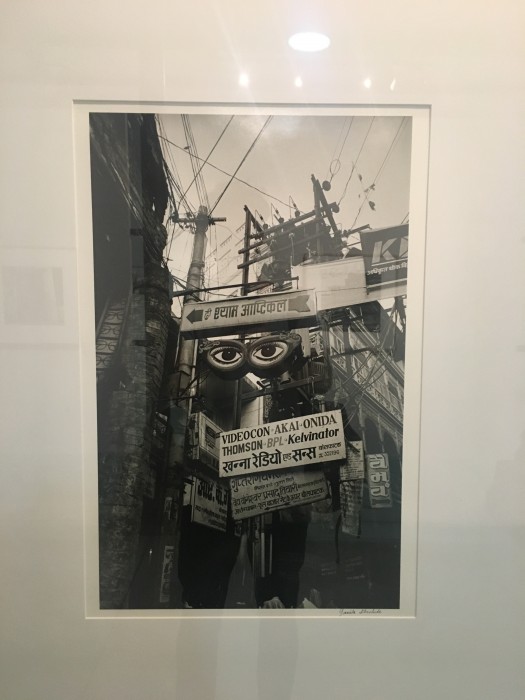

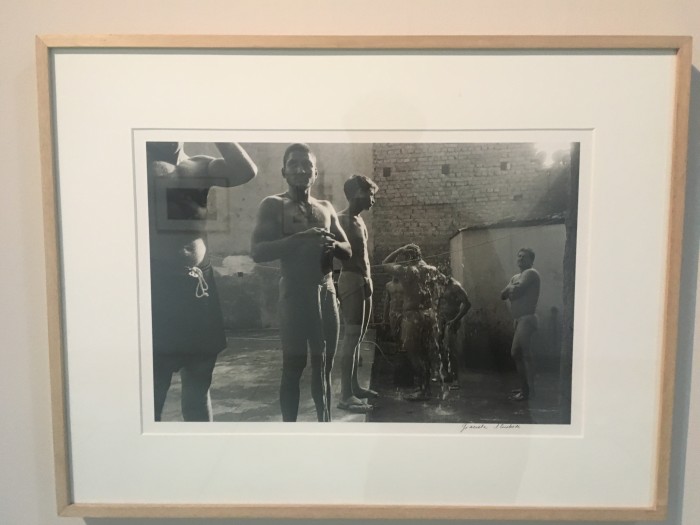

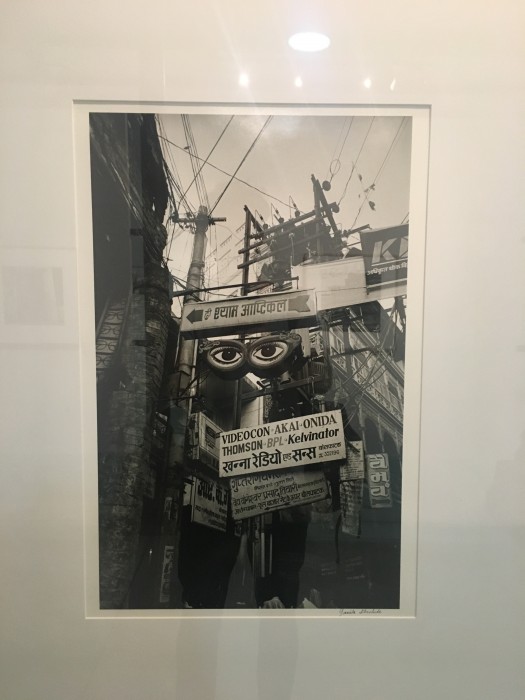

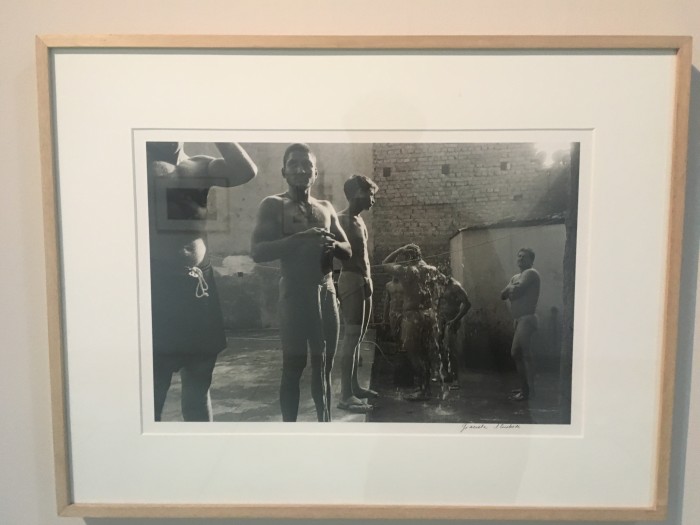

But then other questions emerge. Why was she in India, anyway? What city is this? When was this trip taken? And, going further, what is her interest in the body?

Iturbide photographed an all-male wrestling gym of some sort, and a person going through a transition. She attends carefully to the way that light falls on the body—as if the caress of light on skin were inviting us, too, to a tactile experience.

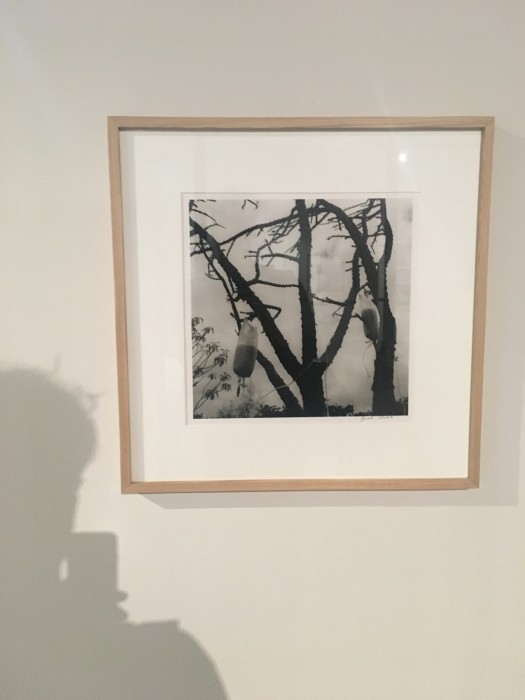

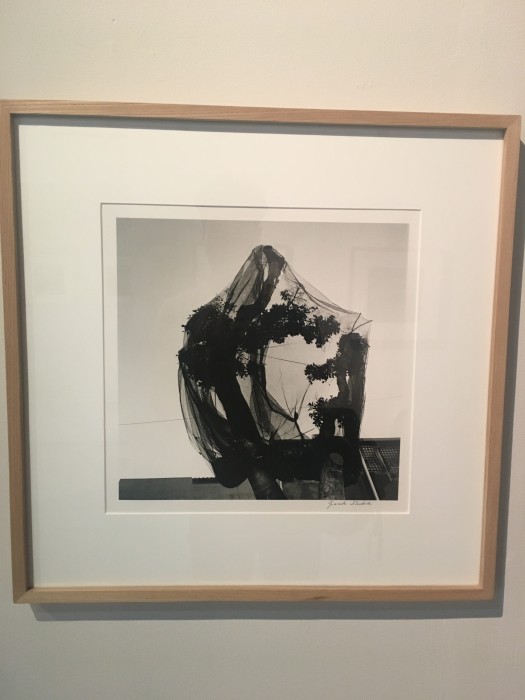

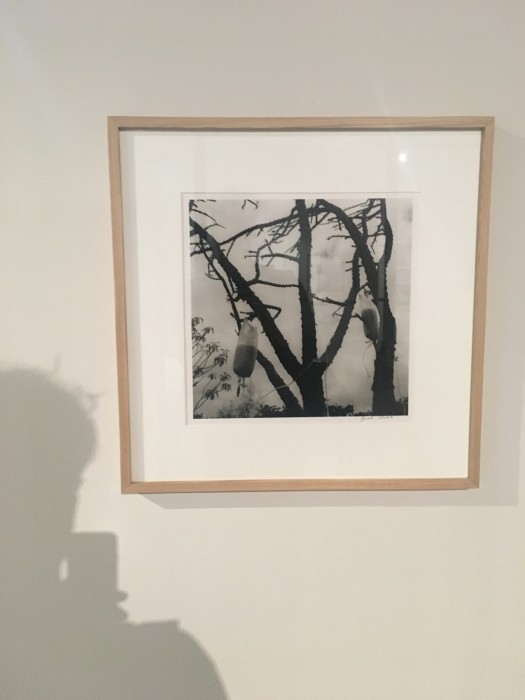

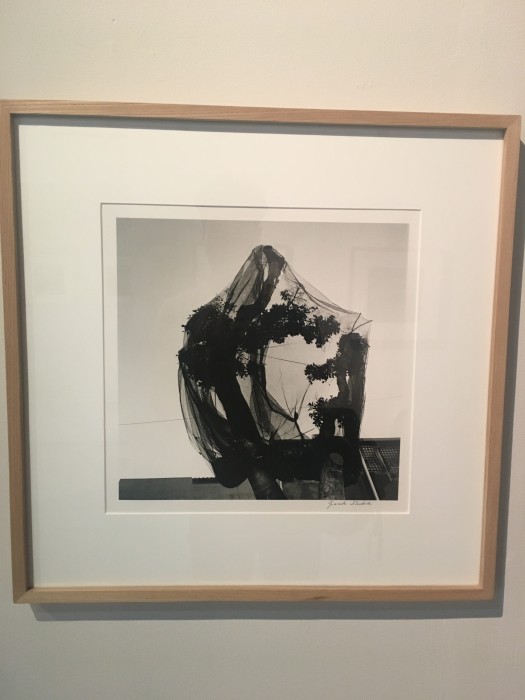

And then, two very noteworthy photographs, in which trees (or cacti? I can’t tell exactly) appear as bodies in need of care. Perhaps here, finally, my historian’s desire for date and place fades away.