This blog post by Zoe Strauss is the best thing I have read in a long time. I’m not even through reading it, but you need to see it. Here are some more links explaining her project I-95.

After American Photo posted a “Best Photo Books of 2011” list, intrepid blogger Ken Iseki posted a comment noting that there were no Japanese books listed. True indeed. So, in a long-awaited Street Level Japan x eyecurious collaboration, we’ve collected a bunch of “best photobooks of 2011” lists… FROM JAPAN. Hope you enjoy.

NOTE: It can be difficult to acquire some of these books if you’re outside of Japan. I’ve added links wherever possible, although in most cases there will be no easy English-language way to track them down. As always Japan Exposures is the fall-back option to acquire anything. If you’re looking for something small and self-published from Japan, Parapera is an extremely good option.

My list

Kazuyoshi Usui, “Showa88” (Zen Foto Gallery)

Maybe my favorite book of the year. Bright colors, geisha and yakuza draw you in, but Usui is very conscious about playing with Japanese culture and history. I will definitely introduce this work in more detail in 2012.

Color photos of Spain in the 1970s that Kitai dug up from his basement. Simple and excellent. I posted a few photos here and they were later picked up by a blogger in Spain who wrote some very nice things about them.

A criminally cheap self-publication which creates an artificial structure for “daily snap photography”—it’s a book of photos only taken on the first of each month.

Color photographs from a psychology graduate turned photographer. You could actually buy this zine using the link above.

Taishi Hirokawa, “Still Crazy: Nuclear power plants as seen in Japanese landscapes” (Korinsha, 1994)

I’m cheating. This book was actually published in 1994, but it’s the most I spent on a book this year, and with good reason.

*****

Nao Amino, editor. Worked at Little More and FOIL, freelance editor and exhibition planner from 2011

Rinko Kawauchi, “Illuminance” (FOIL)

Shigekazu Onuma, “SHIGEKAZU ONUMA” (limArt)

*****

Atsushi Fujiwara, photographer and founder of ASPHALT Magazine

Eiji Sakurai, “Hokkaido 1971-1976” (Sokyu-sha)

Hiroh Kikai, “Tokyo Portrait” (Crevis)

*****

Ken Iseki, website editor and blogger

Masayuki Yoshinaga, “Sento“* (Tokyo Kirara-sha)

“Masayuki Yoshinaga, who has been shooting groups of minority and outsiders in Japan, made this series of work in 1993 when he was still a photographer’s assistant. Building good relationships with the subjects made it possible to photograph these relaxed naked men from such a close distance.”

*Sento is an old style public bath (not a natural hot spring) that can be found almost anywhere in Japan.

Masafumi Sanai, “Pylon“ (Taisyo)

“After publishing tons of photobooks with various publishers since his debut in the late 1990s, he launched his own publishing label ‘Taisyo’ in 2008. Sanai is a very typical Japanese photographer in a way: strolling around neighborhoods and shooting photos without any concept, but no other photographer’s work has as much strength as his photography. This is the tenth book of his own from the label.”

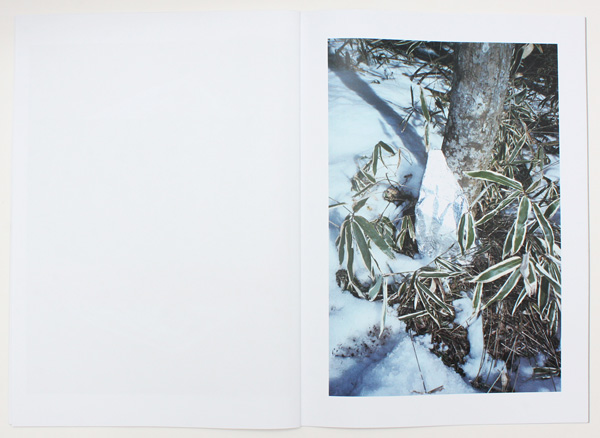

Takashi Homma, “mushrooms from the forest 2011“ (Blind gallery)

“As many other photographers did, Takashi Homma also left for the Tohoku area to document the aftermath. But he didn’t photograph any debris or people like others did, instead he chose to shoot the forest and mushrooms in Fukushima which also suffered from radioactive contamination.”

Kotori Kawashima, Mirai-Chan (Nanaroku-sha)

“Because this photobook reached people who don’t buy photobooks or who are not even interested in photography at all. Simply amazing.”

Masterpieces of Japanese Pictorial Photography (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography)

“The exhibition “Masterpieces of Japanese Pictorial Photography” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography reminded us that there was also an significant movement, which is hardly recognized, before the era of Araki and Moriyama. This is the catalog from the exhibition.”

*****

Ryosuke Iwamoto, photographer

Naoya Hatakeyama, “Natural Stories” (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography)

“For me, the best thing wasn’t a book but an exhibit—Naoya Hatakeyama’s show ‘Natural Stories’ at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. It’s not really ‘today’s Japanese style,’ but I thought it was great on the whole, so I’ll pick the catalog that he made for the show.”

*****

Microcord, blogger

Nobuyoshi Araki, “Rakuen“ (Rat Hole Gallery)

Shinya Arimoto, “Ariphoto Selection vol. 2“ (Totem Pole Photo Gallery)

Hiroh Kikai, “Anatolia” (Crevis)

*****

Tomoe Murakami, photographer and lecturer

Naoya Hatakeyama, “Terrils“ (Taka Ishii Gallery)

*****

John Sypal, photographer, blogger and internet celebrity

“2011 saw the publication of several more photobooks by Nobuyoshi Araki. In addition to being featured in at least one magazine each month, the man puts out more solo photobooks in a year than most established Western photographers put out in a career. Here are three of my favorites and one non-Araki publication.”

Araki, “Theater of Love“, (Taka Ishii/Zen Foto)

“A small visual treat published by Taka Ishii & Zen Foto galleries which is a collection of recently rediscovered pictures taken by Araki in the mid 1960s, several years before his Sentimental Journey debut in 1970. The book, published in an edition of 1000 copies, matches the 5×7 size of the actual rough little prints while the content allows one to see the the very foundations of Araki’s future major themes coming to light. A must-have for those interested in learning more about the early stages of this artist.”

Araki, “Shakyo-rojin Nikki“ (WIDES)

“With a title that roughly translates into “The Diary of an Old Man Photo Maniac”, Araki again employs his date-imprint function to great effect chronicling the three months to the day after the Tohoku Earthquake on March 11th. Where his inclusion of color paints to black and white photographs resulted in brilliant and moving imagery, his alteration of the images in this book was subtractive in his scratching of the negatives with the edge of a coin. Each image bears a scar or fault line through it with results that fluctuate between sadness, horror, and at other times comedy. His tenacious treatment of the actual physical essence of film-based photography comes across as a rebellious challenge to the dry dull digital era he has been lamenting in recent interviews.”

Araki, “Shamanatsu 2011“ (Rathole)

“The third and most beautiful of three Araki books published by Rathole Gallery in 2011, Shamanatsu continues on with the artist’s personal destructive alteration of physical photographs. The book is divided into two parts, the first being pictures taken with his Leica over the past 5 years from various commercial assignments and personal experiences. Each print has been unsettlingly and completely torn in half only to be mended back together with cellophane tape across the front the prints. The publisher did a marvelous job recreating the shimmer of the tape on each page. The second half of the book is a series of images Araki took over the unusually hot 2011 summer with a new Fuji 6×7 camera purchased earlier in the year. In a recent interview in the mens’ fashion and culture magazine, HUGE, Araki states clearly that Shamanatsu is not any sort of Art with deep meaning, but simply the photographic manifestation of his own physiology. He also added that after his new camera broke this series came to its sudden end.”

Meisa Fujishiro, “Mou, Uchi ni Kaerou 2” (Let’s go home 2), (Rockin’ On)

“Photographer Meisa Fujishiro’s sequel to his wildly popular book “Let’s go home”. While his first book, now in it’s 9th printing, simply dealt with married life with his wife (a professional model) and dogs, the sequel introduces his son from birth and five years after that. For a skilled photographer who mainly shoots celebrities and bikini models, Fujishiro’s pictures of his home life are never bogged down by excessive slick camerawork or sentimentality. Their delightful frankness is a simple kind of beauty.”

*****

Ivan Vartanian, author, editor, publisher and book producer

“The books I’ve selected aren’t necessarily “best of” books. Rather, they were selected for what they say in relationship to the photobook oeuvre of each individual photographer.”

Yurie Nagashima, “SWISS+“ (Akaaka Art Publishing)

“From her earliest and strongest photography projects, Nagashima has used Family, her family in particular, as the source material for her photography. As a book production, SWISS+ interleaves pages of photography with prose printed on tracing paper. The photographer has recently turned her attention to writing both non-fiction and fiction. This book most poetically gives us a framework for how she finds a sort of concordance between the two mediums, sometimes independent, sometimes dependent on one another.”

Takuma Nakahira, “Documentary“ (Akio Nagasawa Publishing)

“This book was largely overlooked and under-appreciated after its publication. Documentary compiles this master photographer’s recent color work. The photography’s awkward vertical format and how it reveals the position of the photographer relative to his subject matter seem to be at odds with the book’s lofty title. But when we consider this publication in light of Nakahira’s early and other experimental work, the project of his color work is slightly more understandable—resisting the dogma and trappings of contemporary photography. The publication of Documentary was almost simultaneous with the publication of a facsimile edition of his legendary For a Language to Come (Osiris, 2010).”

Daido Moriyama, “Sunflower“ (MMM Label [Match and Company])

“The lush black and tonal range of this publication are an example of how beautiful basic offset printing can be. The same is true of the craftsmanship exhibited in the book’s layout and edit. In its simplicity, it shines.”

Takashi Homma, M2 (Gallery 360)

“M is an ongoing series of about fast food restaurants around the world. M refers to the identifying logo mark of the McDonald’s chain of restaurants. Such establishments have been a continual object in Homma Takashi’s photography since his Tokyo Suburbia series, which addressed the Americanization of Japanese culture. The screen printing of the photobook’s cover has a plain visual kinship with the discernible dot pattern on the cups and packaging produced by the fast-food chain. Does eating too much fast food also effect vision? Among the 500 copies of the edition, there are multiple cover variations.”

Koji Onaka, “Long Time No See“ (Média Immédiat [France])

“This is a bit of a cheat. This book was not published by a Japanese publisher but, as a body of work, it may be one of Onaka’s best photobooks so far, especially when considered relative to his previous publications. This is an example of the photographer stepping outside of his familiar territory and producing a body of work that is free of his usual rigor. The full weight of his previous work still lingers in the air of this tiny book. It is a treat to see the cone-shaped birthday hat worn by his otherwise hapless mother, dutifully giving her son (Koji) a birthday party. The photographer scanned monochromatic photographs from his family albums and added color to each image in Photoshop. Onaka’s father was a photographer so there was a wealth of snapshots to choose from.”

There’s going to be a shocking amount of 2011-related Japan photography content showing up here this week. Before that, though, I would like to say that Naoya Hatakeyama’s show “Natural Stories” was the “best” show of the year. I wrote a little bit about it for Tokyo Art Beat’s end of year piece. Marc Feustel wrote about it too.

I recently found some photographs that I really liked. They can’t be seen online yet, but I will be talking about them more in the future. The concept of the series is, what if Japan’s Showa period had never ended, and continued up until the present day? For background: Japan uses the Western style year system (2011) as well as the imperial system (Heisei 23). The title of the work was “Showa 88,” because Showa was the period before Heisei, but this is really not important, Wikipedia has more info if you are interested. The point is that, at the gallery talk, someone asked the photographer: “well, you’re calling this work Showa 88, but 2011 doesn’t translate to Showa 88. This year would actually be Showa 86, and you have a photo of the earthquake damage in your book, so wouldn’t people know that you took it this year.”

To which I dimly thought, but did not formulate in time to say: “What a short-sighted comment, as if there will not be plenty of areas that still look like that in 2013, or 2023…”

I’ve never heard anyone else say this, but I dream of becoming a photography critic. So it was with no little thrill that I read A.D. Coleman’s recent essay, “Dinosaur Bones,” [PDF] in which he holds forth on the position of the photography critic—that elusive creature!—in these wild and wooly times. What would he tell me, “go get ‘em, tiger”? Not exactly. According to Coleman, I should probably pack it in, because this train has already left the station. To be more specific, Coleman writes that there are no longer any opportunities for photography critics to find a suitable audience while making a livable wage. So much for that plan, I guess.

I’m joking, of course, but in his essay Coleman hits on something which I think is absolutely correct: that there exists a perception of criticism as a tool designed to surgically remove anything fun from photography and examine it under the cold light of theory. What’s painful is that this perception is not far from the truth. Who could fault anyone for thinking this, when it seems like photography criticism has driven off a cliff of academic cliches? I enjoy theory, but I haven’t yet developed a sensible way for that reading to influence my photography writing. I want to be sensitive about this because too often, the theoretical content of photography criticism comes at the expense of its clarity. Although these two concepts are not mutually exclusive, I can’t point to a critic who is making a reasonable effort to make their work understandable to a broader audience—if you can, please tell me. In short, I think we should be demanding better from people in these positions.

Not as if the situation online is anything to be proud of. Marc Feustel is the clearest writer we have, though his blog has become more and more sporadic. I do look at other blogs, and there’s plenty of interesting stuff out there, but when it comes to serious analysis of photographs, I feel like the writing rarely goes beyond platitudes. No one seems to be developing anything with their writing, or pushing towards something larger—and this is something we could be learning from theory! There’s no need to throw out the baby with the bathwater, but still, let’s scrape the rock bottom of online photography criticism and talk about Visual Culture blog, the internet’s own sad-clown attempt at writing big league criticism. I’ve honestly wondered in the past if this blog isn’t really a sick experiment probing the limits of just how far theory can be twisted to wring meaning out of the damp squib of early millenial photography. It’s not a pretty sight.

Where to go from here? It seems useful to return to Coleman’s original point, which concerns the way that critics support themselves financially. Maybe the pros are writing in code, and the amateurs are only chattering away, but what kind of position between these two poles would offer an audience along with some support? The audience is already out there: really, who doesn’t want to read clear and intelligent writing about photography? The only question is how to create a platform to support the writing. Coleman doesn’t seriously engage with this question, and I don’t blame him; he went panning for gold in a stream which was pretty well stocked until a few years ago. I accept Coleman’s message that we can’t go back to the good old days—the idea of a full-time criticism gig really is just a dream for me. But it doesn’t follow that the institution of photography criticism is doomed. Quite the opposite! If we want, it’s in our hands to make something productive of it.

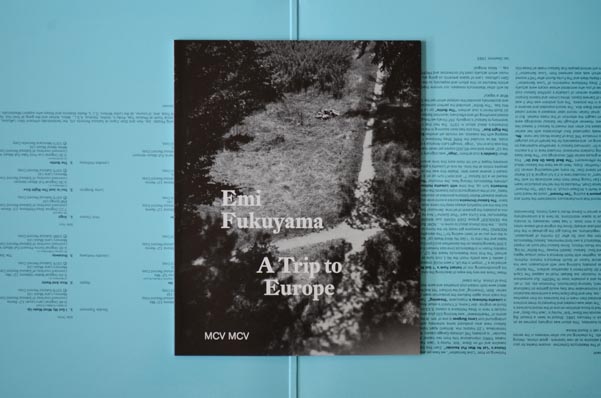

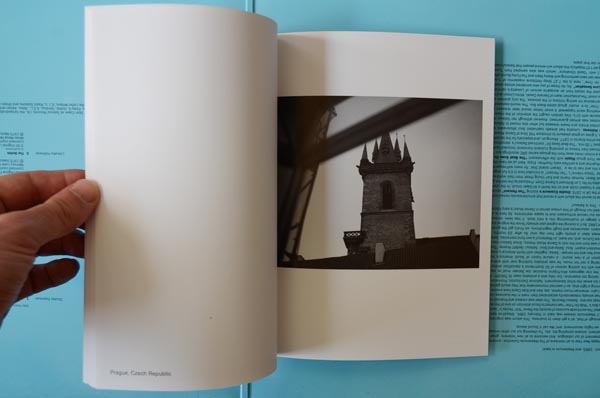

I’m pleased to announce the first title published by MCV MCV, Emi Fukuyama’s “A Trip to Europe.” It’s a small book of photos that Emi took in 2009, while spending a month or so in Germany, France and the Czech Republic. It costs ¥1500 (including worldwide shipping), and you can see more information about it here.

It’s taken well over a year to produce this book, as the project took a couple of different forms. I’m glad to have it out, and I’m looking forward to the next MCV MCV projects. In general, the desire to publish books is similar to the reason for writing this blog, namely to introduce foreign countries to Japanese photography—especially when it’s on a level (street level??) that might otherwise go unknown. Aperture is there to support Rinko Kawauchi, and this is a good thing, but who is supporting Emi?

I’ve recently been reminded of Winogrand’s famous quotation, “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs.” He’s talking in terms of experimentation, and that’s how I see this publishing project. I want to find out what happens when I push the work I’m seeing here out into the world.

Here’s an interview with Rinko Kawauchi, titled “10 minutes with Rinko Kawauchi.” Unfortunately it’s notable for being extremely uninsightful. Here’s my favorite part:

Your photography is truly inspirational. What is your inspiration?

I get the inspiration, for example, while taking a nap, it is a form of meditation.Do people have a common sense of beauty? What is yours?

It is a big, nice question. It is hard to define what is beautiful and it depends on people but I still think we share the same things.

Sometimes email interviews can work out, but this one was dead in the water before it even started. Cue discussion of “Japanese inscrutability.”

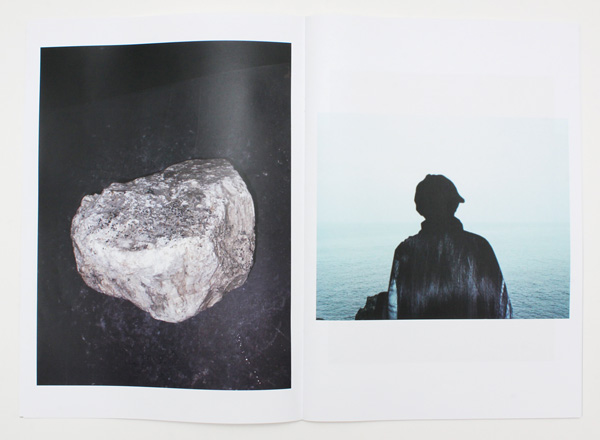

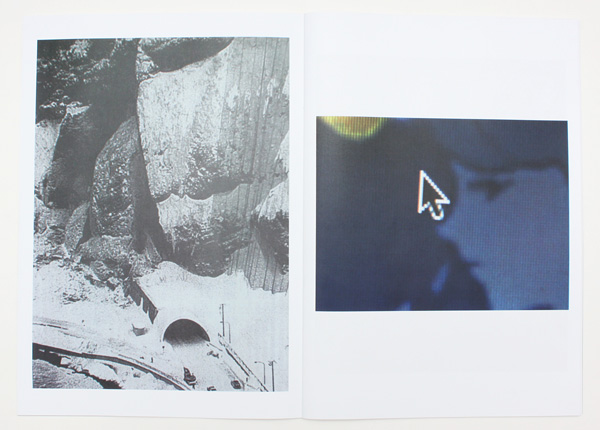

Hiroshi Takizawa had one of the more interesting shows in the “honorable mention” category of Canon New Cosmos. He’s now published that work, called “A rock of the moon,” has a self-published zine in an edition of 50. It’s available for 1000 yen (in today’s US dollars, about $13) through parapera.net.

Parapera is a collective of sorts, they distribute many self-published zines through their site. I can’t be sure of what the shipping costs are outside of Japan, but I guess it can’t be too high. I don’t think they’ve done too much international promotion, which is a shame because they are a very good source of publications that would probably be difficult to find outside of Japan.

Here are some spreads of Takizawa’s zine:

I met Denny Stocks when he first moved to Tokyo this summer. Much like when I first came here, he spent his early days chasing around to as many photo exhibits as possible, soaking everything up. He was, in short, a good dude to chat about with photography. He’d studied in Australia, and worked at a lab, but took a low-key approach to his work. I once heard Denny talk about the photo scene in Sydney, and how it was kind of a messy popularity contest. I thought it could be interesting to interview him about it, and he was game, but when we met up and started hanging out, it just seemed weird. Why force an interview like that with a friend? We spent the time talking about photography instead.

While I got very lucky in finding a work visa when I got here (thanks again Pat), Denny couldn’t catch a break, so he’s headed back to Australia in just a couple of days. Denny and his girlfriend Angelina post pictures together on a blog called Analogues Anonymous, so as a kind of sending-off, they put up a show at 35 Minutes last weekend called “A Gyu Don Life.” It was a good time, as the photo above more or less indicates.

Here are a few of Denny’s shots. He has a strong allergy to social networks, so you’ll just have to stalk his blog for the time being, or use that most ancient of social media, the email. Take care, Denny, hope to see you Down Under (can I say that?) sometime.

A couple of notable posts on Japanese photobooks popped up over the past week or so. First John Sypal reviewed Jun Abe’s “Manila”, then Peter Evans gave an overview of Watabe Yukichi’s work, including his recent publication out of France, “A Criminal Investigation.”

![Daido Moriyama, "Sunflower" (MMM Label [Match and Company])](http://www.eyecurious.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Moriyama-Sunflower.jpg)