What would it mean to write a post here every day? To write posts that perhaps make no sense even to me, but to push them out into the world anyway? To subject them to the (immensely fearsome, in my imagination) scrutiny of an audience entirely unknown to me? I should take it as a good exercise. An important aspect of this blog has been its function as a catalog of my own questions and interests. At this point, I assume that no one reads this blog, that no one checks the RSS feed. Of course I know that this is probably not true, but it feels like a productive story to tell myself anyway. It would be best to push past my doubts.

The website for the Canon New Cosmos of Photography competition includes statements by various judges 1—this year’s crop includes a number of international figures like Alec Soth, Dayanita Singh and Sandra Phillips. I was taken with Shimizu Minoru’s statement, which shows his usual rigor, if not outright harshness:

Abstract catch copy discharged irresponsibly by people who do not look at photographs―words such as “real,” “natural,” or “wild”―is not permitted. Even if it is desirable to take photographs about photography, or to have a good eye for looking at photographs, it is pointless to merely consult the history of photography on its own.

Please be aware that work which relies on context (the death of a family member, the death of a loved one, natural disaster, etc) almost immediately becomes homogeneous. Instead of “a close friend,” select your ideal subject with the utmost care.

Instead of “a photograph of nothing,” show something after thinking, looking, and selecting it with utmost care.

Digital technology is already no longer “something that is not an analog photograph”; it opens on to an unknown territory.

Something that connects this unknown territory to the future and to the past, something that rediscovers “photography”―that’s the kind of expression I’m waiting for.

I think I’ve spent about three years away from photoland. I wonder what I’ve missed during this span of time that’s been filled with academic coursework. My initial guess would be: not much. In the first weeks after the election, I wondered whether anyone within the photography community had published an essay on the relationship between photography and the current political situation in the United States. Nothing was forthcoming then, and I wonder whether there’s anything worth reading now. I suppose my own skepticism about this might open up the question of what the purpose of the “photography community” (“photoland,” as it was called) might be, and what anyone gets from sticking around it.

By now I know that I’m absolutely interested in the history of photography (not “Japanese photography” in particular, not “art history” in general). But as I focus closer on this history, it seems all the more important to guard against the hermetic approach to the medium that I think the term “photoland” captures. Even the most medium-specific of art historians 1 recognize that the term “medium” no longer refers strictly to a technical support. Why not ask what’s outside the borders of this land?

It appears that I’m not actually blogging again after all.

Here is a translation (by Yoshiaki Kai) of the Masashi Kohara essay 1 in Tazuko Masuyama’s exhibition catalog.

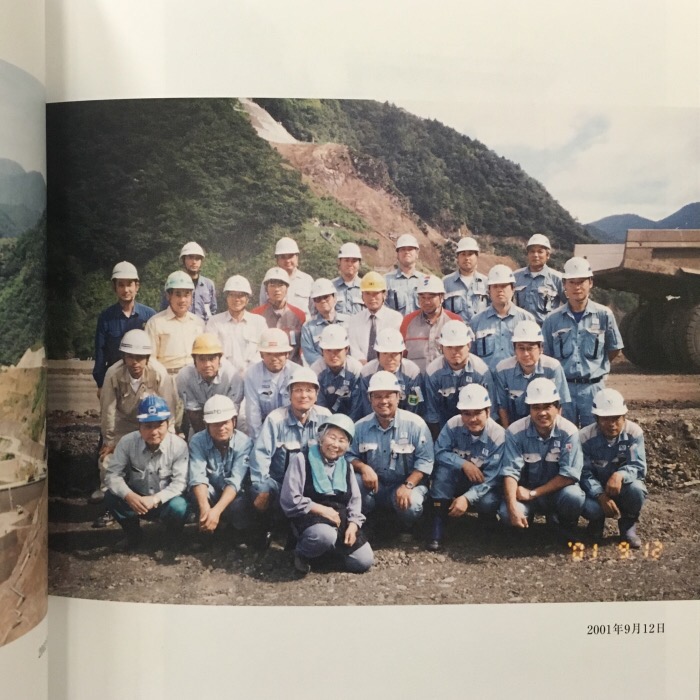

I’m not sure to what extent I’ll use this blog to transmit information about Japanese photography, but in any case I should mention that Takuma Nakahira passed away last year, and that Franz wrote an excellent text about him for Artforum 1. Here are three of my favorite images from his 2011 book Documentary 2.

In a footnote in his dissertation on Takuma Nakahira 1, Franz Prichard points out that Nakahira saw magazines as the “principal battlefield” of his work, and then goes on to argue that art history (when it has dealt with Nakahira) has failed to account for this context:

The sustained impoverished view of Nakahira’s work at the level of photographic art historical discourse contains a two-fold displacement: first his images are extracted from not only the textual practices that accompanied them but also the historical milieu of representational practice with which they were engaged. Secondly, displacing image and text from this crucial ‘battleground’ of periodical media is to sever his work off from the expansive critical horizon of possibility these media embodied for Nakahira.

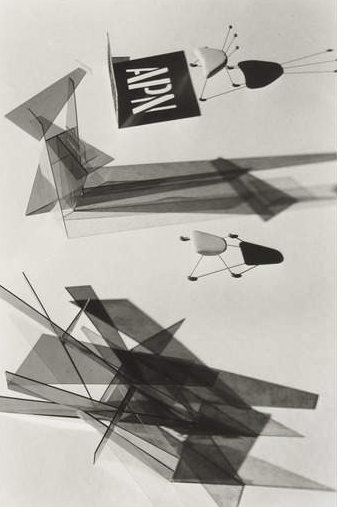

I don’t know what the art historical discourse around Nakahira is like—has anyone besides Franz written on him seriously outside of Japan?—but I can imagine the way in which his images might indeed be separated easily from these two contexts, i.e. the discursive and the material. The implicit challenge here is for art history to account for these contexts, and that’s more or less what I am hoping to do with a short study on a body of collaborative photographs taken largely by Kiyoji Otsuji that were published in the magazine Asahi Graph between 1953-54. A selection of these images currently live in the collection of MOMA 2, where they sit in mattes and look exactly like this:

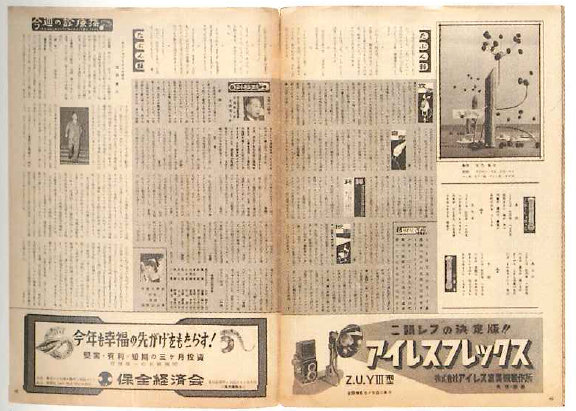

MOMA has a 2003 portfolio that was reprinted from Otsuji’s negatives 3 and sold in an edition of 10. But the photographs themselves, as I said, were published in a broadsheet magazine, Asahi Graph, so in their original context they would have looked more like this:

So one of the first challenges to my study is clear: how should I account for the material context in which this work appeared? What kind of space was Asahi Graph at this time—what else was it publishing? This is the historical aspect of the study. The formal aspect (the more properly art historical aspect, perhaps) will look at what’s going on inside of the photograph. This is something that seems to drive people outside of art history crazy, though maybe these people dismiss formal analysis because that provides them with a justification to avoid doing it themselves. In any case, the formal analysis doesn’t even have to be restricted to the image; it can be linked to the discourse around the photograph and the possible “avant-garde” status of this work.

I have dearly missed blogging. The fact that I’m now in the academy makes it all the more important, I think, to hang on to clear, concise writing—not to suggest that such writing is impossible from within the academy, of course, it’s just not given any special valuation. (No bonus points for the clear writer.) In any case, I am hoping to write on the blog a lot more this year, in order to work through the ideas or questions that are present to me. I am writing for myself, even if I know that some people are actually reading out there. I doubt I will even publicize these posts as I shake the rust off…

It’s winter break, which means that I have a little bit more time to spend on this blog, which does still occupy some corner of my mind. Last year I did not (could not) take any classes on photography, but the time off served me well; it was useful to learn about completely different things. This year I have photography classes right and left, and it has been nice to get back into the swing of things. I’m starting to do research about Otsuji Kiyoji, who could easily become a dissertation topic if I were so inclined—but then it’s more a question of whether Otsuji’s work itself suits my own goals as a scholar.

Otsuji, in any case, is at least tangentially relevant to an essential (not comprehensive) article that came out last week, “Japanese Photography: The Birth of a Market.” 1 And by “market,” of course, we really mean “the European market.” Here is the thesis of the article:

Western collectors’ newfound curiosity about the Provoke artists follows a concerted campaign by a handful of players that demonstrates both how changing tastes alter markets, and how markets can change tastes. That campaign’s success so far rests on a confluence of trends.

These trends are the elevation of once-marginalized photography into the space of contemporary art, various museum exhibitions of Japanese photography, and, naturally, the desire of dealers “to find new sources of affordable material.” In a sense, it is refreshing to see this cynical calculus laid out so clearly, though I suppose one should expect this from a trade publication like Blouin.

There’s a lot to say about what (or who) this article does not address. Still, it’s nothing if not a lesson to anyone ostensibly working outside of the market that your activity is always being watched, and will be snapped up if and when it becomes profitable to do so. By “activity” I’m thinking mostly of writing, whether in blog or scholarly form, but this of course also includes curating, publishing, translating, and so on. I have tried to keep my own activity separate from the art market, but I can’t at all claim a kind of purity here! Even leaving aside the minor success of Daisuke Yokota’s zines on PH, this blog is full of free tips to the enterprising gallerist.

Hester Keijser recently woke her excellent blog up from its long slumber. In her eloquent return to blogging 2, she writes about this very issue of co-optation, which she says was at least somewhat responsible for her break. Hester tells us: “I still have no answer how to prevent others taking advantage of my writing — unless perhaps by producing only what is of little value to them.” This seems like a place to start, or a goal to keep in mind. In the field of scholarship on art, though, what kind of work produces little economic value while also contributing to a broader dialogue? It is easy to see how writing a dissertation on a lesser-known artist creates a new market, but perhaps there are ways to work against that. I’ll dig into this a little more over break if I can get myself back in the blog habit.