- For readers in Tokyo, or visiting Tokyo over the next two months, I highly recommend a visit to Kurenboh, a Buddhist temple in Taito-ku with a small but very well designed photo gallery. The current exhibit is of Lee Friedlander prints, which should be recommendation enough. A reservation is required to see the gallery, but this means that when you go, you’re left by yourself to commune with Friedlander. It’s a unique and worthwhile experience.

- Here’s a preview of Jun Abe’s new book, which looks fantastic.

- OG blog Japan-Photo.info is back and running again, along with a new companion Tumblr.

- The Independent Photo Book is a sort of classified section for small photo publications. It’s interesting stuff, especially the prices. Sight unseen, who’s about to spend 55 euro on a 7×9, 24 page book? And who could say no to a book of the same length for 4 pounds including shipping?

Another day, another link to a post on the La Pura Vida blog. This time it’s to a guest post by Blake Andrews, who is almost definitely the most cogent “recognized photoblogger” of our time.

His post is about the reaction to a stimulating essay by Paul Graham which attempts to find a place for “straight photography.” Blake’s post, and the original essay, are both well worth reading.

I’m interested in the concept of a “straight” photography. For a while I was trying to think of a word that would describe the kind of photography we are naming with the word “straight”—as Paul Graham puts it, “photographs taken from the world as it is.” I thought “natural” might have fit, but that seems to go against the nature of photography, as it were. “Straight” seems accurate, although problematic, but let’s get to that later.

I think a lot of the photography in Japan could be considered “straight.” A glance at the past year of exhibitions (Japanese only, sorry) at the Tokyo Museum of Photography shows that almost everyone is working with the things in front of them—Ihee Kimura, Cartier-Bresson, Sebastian Salgado, Keizo Kitajima, etc. (One notable exception is the Yasumasa Morimura show which is up right now.)

And if Paul Graham points to Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman as figures dominating the Western photo scene, consider the two largest figures in Japan, Araki and Moriyama, both of whom are working in a tradition that could definitely be called “straight.”

Many words from foreign languages are forced into Japanese, sometimes taking on different meaning. “Personal computer” becomes “????” (“pasokon”) and so on. The word “straight” is rendered in Japanese as “?????” (“struaato”) and means “direct” or “frank.” I actually like the idea of describing a photograph as being “?????.” Sexually, the phrase “straight photography” is backwards, and for a type of work which claims to be fighting for a place at the table it can’t help to come off as reactionary.

This post by Bryan Formals on the La Pura Vida blog is worth reading if you are tired of or frustrated by the relationship between “photography” and “the art world.”

Photography enjoys a very comfortable position here. At a cultural level, there’s a great awareness of photography in general. This may have something to do with the serious amateur photographers who have a strong public presence. Thinking on a smaller scale, “photography world” itself is wide enough that different schools of thought are able to exist together. The issue Bryan is tackling may not apply too strongly to Japan, but the way he approaches it should ring true for anyone trying to push things forward.

“I just think there’s nothing more satisfying than the narrative thrust: beginning, middle, and end, what’s gonna happen. The thing I’m always bumping up against is that photography doesn’t function that way. Because it’s not a time-based medium, it’s frozen in time, they suggest stories, they don’t tell stories. So it is not narrative. So it functions much more like poetry than it does like the novel. It’s just these impressions and you leave it to the viewer to put together.”

I would like to start this post by introducing the word “Akaakaesque,” a term coined after the art book publisher Akaaka-sha. Akaaka has established a strong point of view for themselves in photography books, and while not every book they publish is actually Akaakaesque, they are consistent about publishing color work which is highly personal, to the point of willfully excluding the “real” world, or the one outside of the photographer’s head. In cinematic language, this might be close to cinéma d’auteur—damned if the photographer’s going to let anything get in the way of their vision.

Aya Fujioka’s “I Don’t Sleep” is published by Akaaka-sha, and it strikes me as extremely Akaakaesque. Events in Fujioka’s life push this book along, and more than an exploration of photographic technique or “photography itself,” they provide the tension which makes “I Don’t Sleep” quite difficult to put down once you’ve started looking at it. These photographs document a family trauma, and it sometimes seems as though Fujioka wants to grip the viewer, hold them up to her experience and not let go. If this sounds uncomfortable, it can be, but the book’s palpable intensity really sets it apart.

What makes the work so strong, though, is that Fujioka does not generate this intense effect through an exploitative or overly sentimental treatment of her subject. On the contrary, she has made an honest effort to communicate her experience as clearly as possible. If the work is not actually, as it were, clear, this isn’t because Fujioka set out to make a vague book.* The structure of “I Don’t Sleep” provides some insight here.

The first half of the book establishes Fujioka’s photographic style: basically, a refined snapshot. To be successful, snapshots usually rely on a tension between elements in the frame, and there is certainly tension running through these images: we see the strange combination of a flower bush and a staircase, a stray branch filling out the composition of an empty scene, and a fractured vista signboard in front of view it’s supposed to represent. In each case, the images have a tenuous balance; this is particularly true of the flower and the staircase, whose equal weight within the picture strikes me as quite strange. There are slight indications that the photographer is traveling somewhere, with someone else, but still, these photographs don’t indicate what’s happening.

The second part of the book addresses the central trauma more directly, and brings home the intensity of Fujioka’s experience. Up until this point, the book is edited like a collection of snapshots; there’s always a clear change of place and subject from one page to the next. But the second part starts off breaking this rhythm, with two separate 8-page digressions, each showing a series of one thing, all taken from similar perspectives. (You can see some of these photos in the Japan Exposures gallery.) These digressions come as a shock, certainly with respect to the pacing and editing of the book, but also because they it reveal the reason for Fujioka’s journey, and maybe also why she “Can’t Sleep.” They almost make a red herring out of the first half of the book—its delicate tension can be read differently in this new light, but it seems more like a foil for the second half, a kind of misdirection to bring you in close before revealing something darker. These two passages make the intensity of Fujioka’s experience clear.

After Hiromix, there have been any number of books published in Japan of color snapshots, especially by women. But “I Don’t Sleep” distinguishes itself from this crowd through its tight sequencing: the book has a beginning, middle, and end, always striving to maintain clarity in the face of severe personal stress. It’s an impossible task, of course, but as a method it yields compelling results. “I Don’t Sleep” is more than just Akaakaesque—this word imparts nothing of the coherency of the book. There are dramatic events here, but no dramatic effects. “I Don’t Sleep” came out in late December of last year, which makes it either the last essential book of 2009, or the first essential book of 2010.

Available at the Japan Exposures store.

* We could say that each photo is like a musical note which needs to be arranged to create a coherent piece of music. On its own, the photograph has only a tangential relation to experience. The work might have an internal coherency, but even then, expecting it to have some meaningful relationship to experience is like hoping for a spiritual revelation after sending some holy book through a game of “telephone.” (Which doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen)

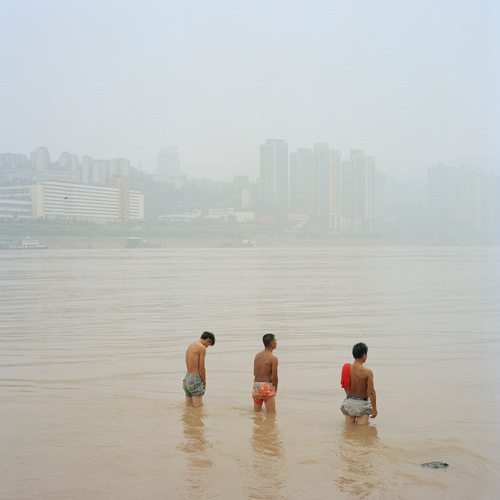

I enjoyed Mu Ge’s January exhibit at Zen Foto Gallery, “Go Home.” Now in March, Zen Foto is showing “Still Lake” by Liu Ke (??), another photographer from Chongqing who also takes 6×6 photos by its rivers. (The two photographers are friends in real life.) Although their work is naturally close, the differences between them go beyond the fact that Mu Ge uses black and white and Liu Ke uses color.

Most of Liu Ke’s photos can be placed into one of three groups: portraits, conditions (i.e. of Chongqing) and abstractions. Mu Ge’s work consists mostly of these first two categories, and I think that right now, his portraits are stronger than Liu Ke’s. As for “conditions,” this is where the two are closest—each show human activity at the scene of Chongqing’s rivers.

But the abstractions are where Liu Ke breaks from Mu Ge: at times, he forces a strong composition on his material. The image of a lone bus in an otherwise empty scene is compelling, and it wouldn’t have any place in Mu Ge’s world.

The bus is actually one of the strongest motifs running through Liu Ke’s work, and it becomes another backdrop against which to observe people. The photos of people sitting on buses are some of the best photos in Liu Ke’s portfolio. They’re often craning their necks out the window, looking towards something that’s hidden from the viewer.

There can be a lot of ambiguity with Liu Ke. Why is this shopkeeper covering his face? And what’s happening on TV?

I don’t think it’s coincidental that this photo was taken away from the river. It seems as though if you’re in Chongqing and take a photo of something by the river, there’s a good chance that an unexpected element—power lines, a boat, a half destroyed building—will creep into the frame, just due to the loose distribution of human material in this area.

Liu Ke’s work is actually weaker when it asks this material to carry the weight of his photos; the ineffective image of a woman walking on a dam comes to mind here. By contrast, the shot of fireworks through a window creates a very strong impression. As Liu Ke looks away from the river, he develops a personal and thoughtful style which is certainly worth following. I recommend looking at his prints and portfolios, which will be up until March 24 at Zen Foto.

Is anyone using Google Buzz? Right now I’m less interested in it as a social platform, and more as a way of having private discussions. I am thinking of cultivating a small Buzz group to talk about photography things. If you’d be interested let me know, either in the comments or by email: dan [at] mcvmcv dot net

I am working on a longer post about Fujioka Aya, but here’s a link to a Japan Exposures post I did with John Sypal about her recent book “I Don’t Sleep.” Japan Exposures is also hosting a gallery of her work.

I met Takiguchi Koji at an event last week and was really impressed by his newest series “PEEP.” I think it takes a special photographer to make an entire series of portraits hold the attention well, but “PEEP” is very compelling—at times hilarious, at times tragic, but never boring.

I’m talking with Takiguchi-san to see about featuring some of his work here, but in the meantime I’m highly recommending a visit to his website.

On the subject of new Tumblrs, and the challenge of broadcasting Japanese photo culture through the internet:

Japan Exposures has just made an impressive social media push, both on Twitter and Tumblr. Like Aya Takada’s Tumblr, these accounts are essential following to know what’s happening with Japanese photography. I’m blown away by the amount of interesting links passing through JE’s Twitter account, will there ever be an end?

Conscientious wrote an internet blog post about Ishiuchi Miyako’s Hiroshima and had the chutzpah to call it a “review.” Let’s think about whether this is deserved. Here’s the first sentence of the post:

“The 20th Century was filled to the brim with atrocities, war, and genocide.”

O rly? It would make just as much sense to write a sentence beginning with “Since time immemorial,” or “Throughout history.” Either way, this is a cliche. First sentence of second paragraph:

“Photographers have a long tradition of trying to deal with suffering, to try to convey what it might have meant for those who perished.”

Again, this doesn’t really mean anything, and it could be equally true of painting or sculpture or literature. We still haven’t heard about the work at all, but that’s coming in the next paragraph:

“Miyako Ishiuchi’s Hiroshima, which I first heard about through Marc and which I just found in a Japanese book shop, is another example. Hiroshima shows clothing and personal items worn by victims of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. There are about 19,000 such items in the collection of the city’s Peace Memorial Museum, and the book presents a tiny fraction of these. At the very end of the book, there is a list of the presented items, along with the names of the victims (where they are known).”

So now we know what’s in the book. And the photos themselves, pray tell? Maybe the next and final paragraph will tell us:

“It is left to the viewer to deal with the images, there is no further text (apart from a short statement by the photographer), no explanations, no descriptions. Where words must fail, can images tell us something? I think they can, once we realize that what they might tell us is what we are able to tell ourselves.”

Oh. Actually, as you now understand, it’s left for someone other than the writer to “deal” with the images.

So, where’s the beef here? Why is there no engagement with the work? What makes these muddled thoughts a “review”? At some minimal level, shouldn’t a review communicate the writer’s impressions of the thing they are claiming to tell us about? “Once we realize that what they might tell us is what we are able to tell ourselves”—what does this even mean? Can anyone parse that sentence? (In all fairness it could just contain a typo)

Beyond this one review, why do so many people continually reaffirm the authority of this writing? Online, any blogger can say “this is a review” (”I am a curator“), and the responsibility of deciding whether to take this statement at face value falls on the audience. How will this audience lose its sheep-like qualities, when acting in bad faith—saying nothing means saying “yes”—is so much easier?

This post was a missed opportunity, because it’s worth saying something (anything!) about Ishiuchi’s photographs. She manages the difficult task of conveying the scale of the atomic bomb’s effect without beating the viewer over the head. The entire book is photographs of clothing and mundane objects recovered from Hiroshima (yo this is a link to a site where you can see a number of these images), and I have to admit that when it was described to me verbally I imagined that the work might have been cold, if not even boring. But this isn’t the case at all.

Ishiuchi’s presentation of these objects makes a quiet but clear statement about the magnitude of the atomic bomb. Each thing is recognizable, but has some visible sign of destruction. Ishiuchi photographed these objects against a plain background, and by removing any kind of identifying context, the viewer has to imagine how their particular kind of damage came about. In some cases, it’s possible to make out obvious burn marks, but others are less clear: the fabric of one garment has an eerie lightness to it which certainly did not come from overuse. A schoolgirl’s uniform with alien-looking holes ripped clear through it doesn’t need an explanation.

It’s not easy viewing, but Hiroshima is a carefully considered portrait of August 6 which is well worth seeking out.

NB: Marc Feustel’s post about photographic responses to Hiroshima is a good read for more on this subject. Also, August 6 falls around Japan’s obon week, a festival to remember the dead. I rarely have extended conversations about World War II here in Japan, but I was struck by how often the topic came up during that time, and I saw Hiroshima in that context.