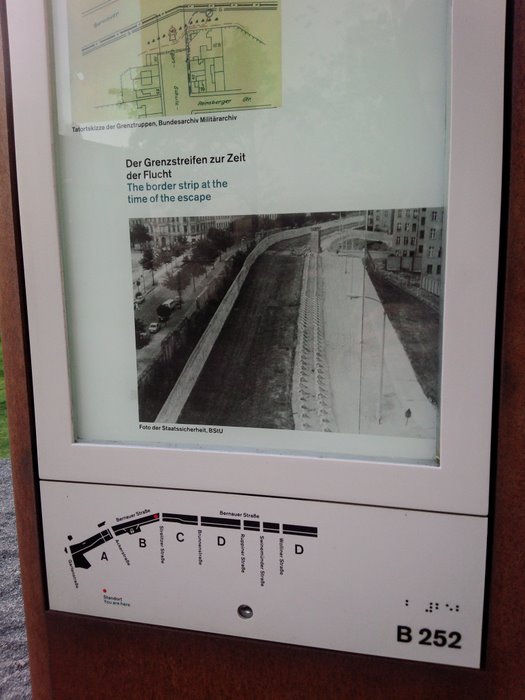

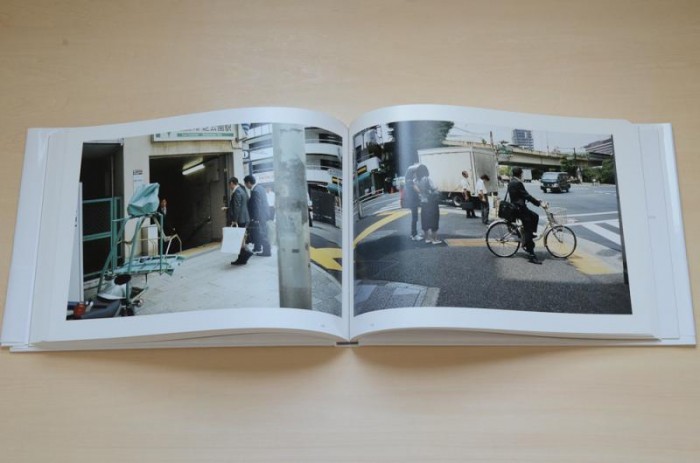

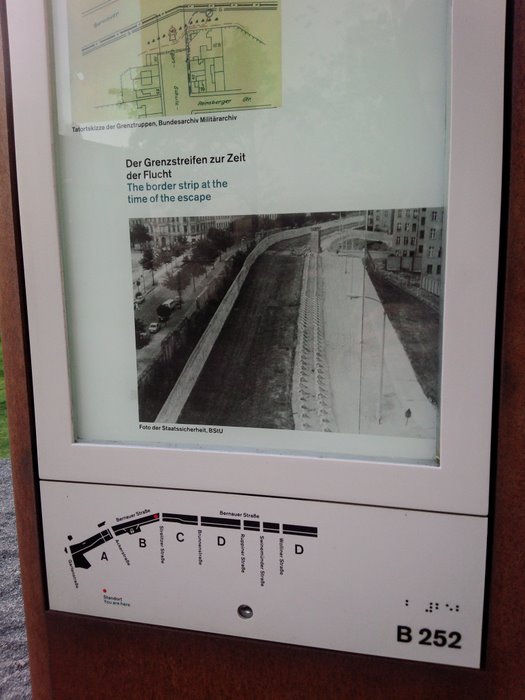

Last month I spent a week in Berlin, and I was struck by the frequency with which the city reminds you of its history. It seemed impossible to walk more than 200 meters without finding a plaque or memorial commemorating something about Berlin’s past. Of course it wasn’t just the city itself: Berliners (the ones I met, at least) were also conscious of this history, and in particular the history of World War II bombings. When I told people the name of the street where I was staying, I often heard something like: “Ah, Alexandrinenstrasse… There’s not so much there, huh? It was completely bombed out in the war, you know.” Naturally, this experience gave me pause to think about how my home city—home for a few more weeks, at least—more or less ignores its own history. Tokyo, after all, was also razed during the war, yet apart from a small memorial there is hardly any visible trace of this fact today.

Of course, Tokyo is now so densely packed that plunking down a memorial in a central location would probably be quite difficult, and (to my limited knowledge) there are no longer any patches of undeveloped land as a result of WWII bombings. Still, I can’t help but think that the city’s own lack of awareness about its past extends to its residents: my own experience really must be taken with a grain of salt, but I have never had any sort of conversation about Tokyo during the war, or in particular the firebombings of March 10, 1945. (I am told that certain groups gather to remember this day.) In any case, when I came back to Tokyo, I was curious to learn more about this significant event which seems to have been put out of sight, out of mind.

I was glad, then, to receive an email from my friend David Fedman with a link to his latest research paper, written together with Cary Karacas, “The Optics of Urban Ruination: Toward an Archaeological Approach to the Photography of the Japan Air Raids.” This paper seems to me extremely well-researched and, quite happily—despite its cumbersome title—highly legible to a non-academic audience. The information that Fedman and Karacas have unearthed, which ranges from the development of aerial photography to the specific methods the United States military used to analyze photographs of Japanese cities, is highly suggestive. Free of any clumsy theorization—an academic specialty, of course, check back with me in a couple of years—the presentation of this material shows very clearly how photography can be integrated into military strategy.

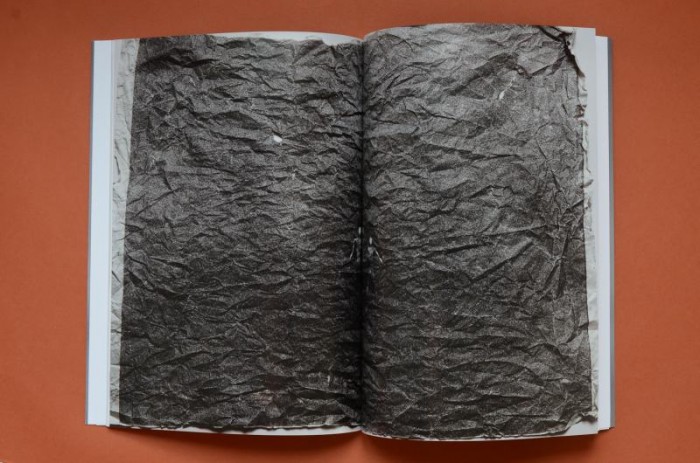

Yet this research does not focus only on the aerial, i.e. American perspective; it also analyzes the photographs of Koyo Ishikawa, a photographer in the employ of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police who is perhaps the only person to have photographed the immediate aftermath of the March 10 bombings on the ground. It sounds like Ishikawa has only been given the most cursory of treatments by historians up until this point, and his photographs have been un- or mis-credited even when they were published. (I was happy to read about the history of Ishikawa’s reception, not just by civilian audiences but indeed by the American military itself.) Fedman and Karacas are successful at showing why this, ah, Street Level perspective is necessary for understanding such an event.

The paper’s weakest point is probably its analysis of the reception of Ishikawa’s unflinching photos at a personal (or phenomenological) level, in other words the effect that looking at such images creates in the viewer. Still, this is a work of history, not art theory, and to investigate such a question thoroughly would be a different kind of work altogether. On the whole, I think this paper will give readers interested in photography—not just Japanese photography—a lot to think about. It’s also worth mentioning that Karacas runs a site, japanairraids.org , that offers further information and links to other talks and papers on this subject.