Ryudai Takano at Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

The Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art is putting on a group show entitled “Photography Will Be” 1, which seems to be a “state of the medium” exhibit; I’m back in America now, so unfortunately I can’t see it for myself. The participants include Yuki Kimura, Kazutomo Tashiro, Naoya Hatakeyama and Ryudai Takano. The show has appeared in the news recently, after police asked the museum to take some of Takano’s work down on the basis that, because it shows male genitalia, it violates obscenity laws. As you can see in the above photograph, the museum is not exactly complying with this request.

I started to write up a post about this incident a few days ago, but since then a lot of material has appeared online, including a statement from Takano that explains the situation in detail; I have translated it below. This post has grown quite long, so I have organized it so that you can first get the general idea of the case at the beginning, then see Takano’s statement, and finally, if you are so inclined, get some background on a different time Takano covered up his photos.

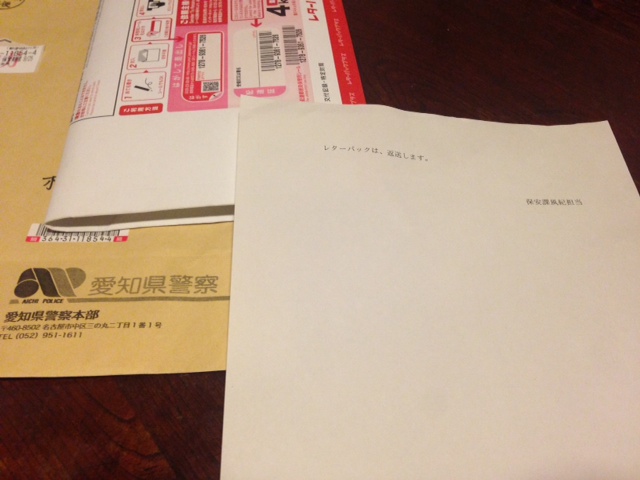

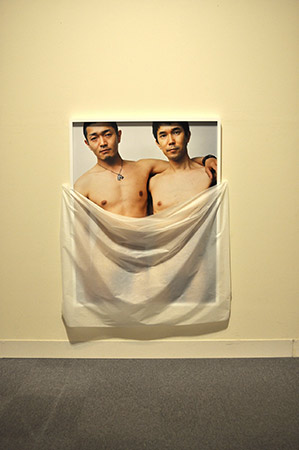

It should be helpful to publish some basic facts about the incident. Takano, who is gay, is showing his work “With Me” (おれと), a series of photographs in which he poses naked together with another person. Most installation photographs online show Takano with a man, but the series also includes photographs with women. The photographs are mounted in various frames that fit snugly next to each other. These images aren’t amazing but they at least give some idea of what the space looks like:

Photos by Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

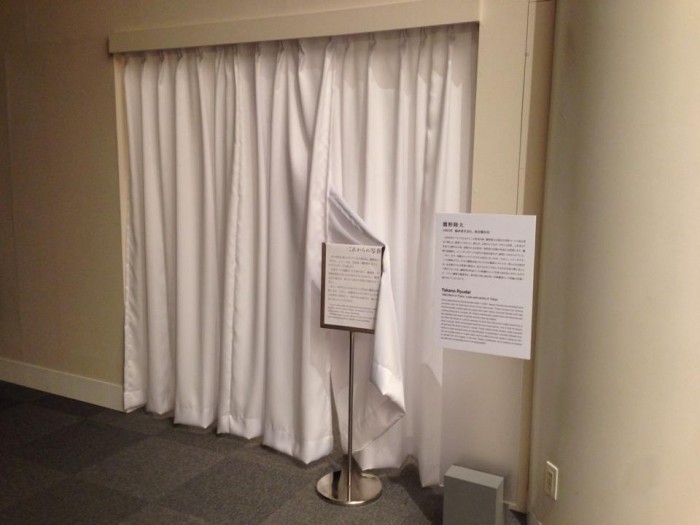

Of course these photos were taken after the police intervention. However, the entrance to the space itself looked like this from the very beginning:

Entrance to Takano's room, photo by Mika Kobayashi

After consulting with a lawyer before the start of the exhibit, the museum had cordoned off Takano’s exhibition space with a notice that explains the content of the works inside. Obviously this did not help in the end, because the police received (and acted on) an anonymous complaint about the show.

Further information about the incident has been provided in English by Artinfo 2 and Japan Trends 3, which also points out double standards with respect to the application of obscenity laws in Japan. Meanwhile, Takashi Arai, another photographer participating in “Photography Will Be,” has created a petition on change.org 4 asking for transparency from the Aichi Prefectural Police which includes an English explanation; as of today it has received more than 1,800 signatures.

As many news sources (in Japanese and English) have pointed out, this incident comes only a month after Japanese artist Rokudenashiko (real name Megumi Igarashi) was arrested for distributing 3-D printer files of her vagina 5; she was later released. Takano refers to this case in a statement about this affair that was originally published in Japanese by WebDice 6. Here, he explains the way in which he responded to the police intervention and reflects on the broader implications of the incident. I think it is well worth reading this statement in full.

After receiving anonymous reports, a member of the prefectural police came to the museum on August 12. Upon examining the exhibit, he concluded that the works were in violation of the law; his judgment was that the public display of a penis is uniformly illegal. He explained that if the exhibit was to continue, arrests would be unavoidable. Because it was not me, but rather the museum staff, that would be arrested, my options were limited.

I had three choices. First, continue with the exhibition as before. Second, remove the specified works and replace them with unproblematic ones, making it seem as if nothing had happened. Third, make it clear which works had been targeted and continue the exhibition in that way.

If I were dead, or if for some reason another person had to act on my behalf, the first and second choices would be possible ways to continue with the exhibition. However, since I am alive and can respond to this matter directly, I decided to alter the exhibition in order to show how this intervention took place. In this way the audience, too, can consider the situation.

While carrying out the work of covering the “improper” parts, one of the museum workers mentioned that this was similar to the case of Seiki Kuroda. In the Meiji Period, when Kuroda (who had returned to Japan from France) displayed a painting of a nude woman, the police judged it to be obscene. The woman’s waist was covered in a cloth, and the affair became known as the “Loincloth Incident.” We are now more than one hundred years on from this incident, and perhaps the fact that the object of concealment is now a man shows how times have changed. In any case, I did not cover these images in a loincloth, but rather from the chest down, in a way that suggests being wrapped up in a blanket.

Aside from my involvement in this case as the creator of the work, I personally think that it represents a violation of the “freedom of expression” (or perhaps the “freedom of speech”) of museums. Artworks are fundamentally “strange things,” and a museum is a place that collects and stores them. If that is the case, then it is natural that a museum should operate according to standards that are slightly off from those of society; in other words, the museum is necessarily an extraterritorial sanctuary. A failure to accept this point means denying the institution of the museum itself. Nevertheless, this time a single “anonymous report” was enough to prompt the intervention of the government. Essentially, a museum is a place that should not be easily entered by government agencies, and I was startled by this lack of respect for art. This is, of course, also an issue for citizens, who operate this prefectural museum. As a place for “strange things,” in other words by supporting diversity, the museum functions as a safety valve for society; citizens maintain and administer the museum in this knowledge.

Recently, a law has been passed that makes it easier for the government to involve itself in universities. I think that, in art just as in scholarship, doing away with the limits of such activity will indeed leave an effect. When it is easy for the government to intervene in matters of “knowledge” [知, the “chi” of “Aichi” (愛知), which incidentally means “love of knowledge,” though the Japanese word for “philosophy” is different], it is not difficult to see the danger for a further escalation of that violence.

Saying all this, I am somewhat worried about the possibility that people will cower in fear, though in the decision handed down in the case of the Mapplethorpe photobook, the Supreme Court wrote: “There is some obscene work mixed in here, but looking at the whole, the proportion is low. Therefore, it is not possible to classify the book itself as obscene.” This means there is a precedent to reverse such a judgment through the question of proportion, while the fact that Mapplethorpe’s photographs were taken in black and white was another reason that the work was judged to be art, rather than obscenity. However, while in many works the relationship between “art” and “obscenity” is an intermingled one, making such a dichotomy impossible, the court has set the precedent that arrests can indeed be made on the basis of an arbitrary judgment of obscenity.

From the very start, though, I cannot comprehend why “obscenity” is a crime. In our mature society, it is undeniable that a naked body possesses absolutely no destructive power. In another similar case which resulted in an arrest, I do not understand at all what the government was up to. I only know a bit about this work, but it looks to be entirely human, not at all destructive. If we are going to talk about expressions that “harm society,” there are any number of more serious examples, yet the expressions that the government continually tries to expunge are entirely proper manifestations of human desire.

In any case, one thing is clear: the government is asserting its presence forcefully through the exercise of such power. If the government deviates from its stated purpose, i.e. to temporarily borrow authority from its citizens, and instead makes a display of this power, that act is far more grotesque than something like the display of genitalia. Once a violence that is not locatable to a specific person begins, it is difficult to stop.

I earnestly hope that museums will be able to run without any self-imposed restraints stemming from this case.

August 17, 2014

Ryudai Takano

I have little knowledge of the way museums are operated in Japan, though it is not difficult to imagine that “self-imposed restraints” are quite common. I recently had a conversation about the MOMAT’s excellent (and, relatively speaking, politically radical) permanent collection 7, in which I heard that the curators are not able to trumpet it too loudly. In light of all this, it was refreshing to read the following statement by a museum staff member given to Tokyo Sports 8:

We do not think that the works are “obscene.” If we were to follow the orders from the police to remove the works, that would be an acceptance of this judgment.

That’s a pretty strong stance to take, even though it—like the initial complaint about Takano’s exhibit—was delivered anonymously. (The vice-director of the museum went on the record with Mainichi 9, using less bold language.) If Takano is right, and the government continues to encroach on the territory of art, how will other museums respond?

In any case, this isn’t the first time that Takano’s work has been covered up; a similar thing happened when he showed his work in Hikarie, a then-newly-opened shopping center, in October 2012. Then, I wrote 10 that the exhibit was “mostly forgettable, except for a long vertical strip of paper over Takano’s largest (and most explicit) photo. I thought it had been placed by the gallery to spare passersby the apparently unthinkable trauma of seeing a male organ as they took a break from shopping, but it was actually Takano’s own choice.” I’d spoken with Takano after seeing this show, but in writing this post I wanted to make sure that I had understood him correctly at that time.

Takano at Hikarie, photo by Lammfromm

The short answer is that yes, this was indeed entirely Takano’s choice. He started his email by saying: “It is not that I think showing a naked body at any place and at any time is a good thing. The same goes in photography, as well.” He went on to explain the particular situation of the Hikarie exhibit: “I am concerned about the people represented in my photographs. Despite the fact that the photographs were shot behind closed doors, when they are displayed in a public place like Hikarie, any number of people will find themselves in front of their nakedness. Even though a subject who comes in for a shooting understands that they will be displayed in public, I don’t think that means they accept this kind of situation. More than anything else, it is not acceptable for them to be subject to the prying eyes of insensitive people.” Naturally, Takano says that the situation of a museum, where visitors pay to enter the space, is different, and that in the case of the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art the museum staff was quite understanding.

Takano’s response to the police intervention is meant to bring his audience into this situation, so I think it is appropriate to give one of the paying visitors to “Photography Will Be” the last word. Curator and author Mika Kobayashi relates that, when she visited the exhibition, she overheard an older man berating a museum employee: “I came here because the paper said there would be something obscene, but they’re just regular photos! And I paid 1100 yen for this?”

Update 9/25/2014:

Takashi Arai updates the change.org petition with a Kafkaesque episode. After gathering physical signatures and sending in the printed petition to the Aichi Prefectural Police, he received a one-line letter from the office (“We return the letter pack”) along with the unopened envelope.