This post comes ahead of Koji Takiguchi’s exhibit “PEEP,” which opens on May 10 at Tokyo Visual Arts Gallery and runs until June 5.

Koji Takiguchi is a young photographer from Yokohama who looks to be on the verge of breaking out. He won a Canon New Cosmos Prize in 2004, winning praise from Nobuyoshi Araki. In 2008, he published “Sou,” an unflinching, often difficult look at a number of events in his family life: the death of his wife’s parents and their cat, followed by the birth of his own child. Two years on from that project, Takiguchi is in the middle of a new series, “PEEP.” This work should earn him a new level of appreciation within Japan, and hopefully outside of it as well. “Sou” is remarkable for its direct approach to Takiguchi’s own pain and joy, but with “PEEP” he has distinguished himself from many of his contemporaries by making a similarly direct inquiry into questions of class, happiness, family, work and vice in current Japanese culture.

“PEEP” is a series of portraits of Japanese people, where each person is photographed three times: in their home, at work, and at play. This approach seems well suited to Japan, where one’s private life is often kept hidden from view.* Photographing a person wearing these three different masks, so to speak, might seem like a good way to “reveal” who they are. And indeed, in his statement for the series, Takiguchi claims that the concept of “PEEP” is to avoid a “one-sided only” approach, and allow the subjects to “have self-direction and stare back” at us.

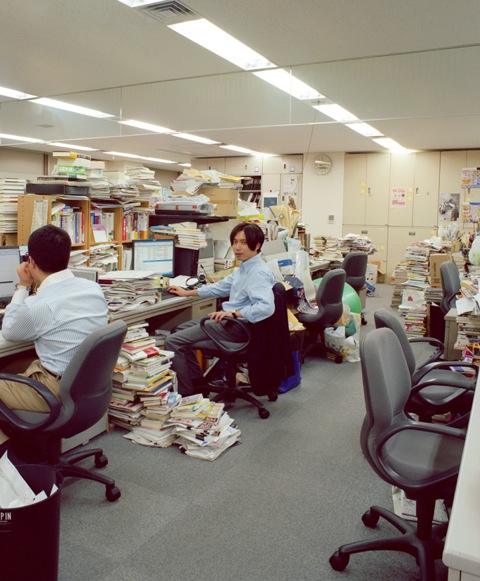

“He edits an economy magazine. He has lots of hobbies, including reading books of course, but he is also interested in collecting music (records, etc.) and various subcultures. Besides cultural activities, he also likes table tennis and it seems he sometimes exercises in order to alleviate stress. I think he is fully enjoying a life on his own.”

In other words, despite its title, “PEEP” is not meant to be an exercise in voyeurism. Takiguchi is very deliberate about the way he photographs his subjects, to the point of making his own disruption into their lives clear. After all, he is something of an intruder: he has to follow them into their home and workplace, then set up a large format camera and snap away! After going through such trouble, how would it be possible to let someone have “self-direction” while trying to shoot a candid photo?** So the subject always looks directly into the camera; they can control the way that they represent themselves, which allows the viewer a chance to meet their gaze comfortably.

“He’s been working at a dating website for a long time. He’s dreaming of musical activities in an indie band. It seems like a lot of the people who are active musically are employed at places like dating websites. Work is work, and he’s doing that work in order to do things he wants to do and make a living.

The friends in his area know what his job is, but they don’t seem to know what he does in a concrete sense.”

In that sense (i.e. as a concept), “PEEP” functions properly, but there’s more to the series than Takiguchi is letting on. This work documents certain material realities of contemporary Japan, without using a photographic vocabulary of “this is good” or “this is bad”—as if we could say those words with a straight face anyway! The power of this series comes from the tension that exists between the roles one must play in society; namely between one’s work and everything else, because at any time, work can demand sacrifices against one’s will. Group activities can create similar demands, with almost as much power behind them, not to mention one’s obligation to family.*** In the face of this condition, how do people enjoy themselves? What relation is there between class and happiness? Is there any connection between work and play? What does having a “good” job do to someone’s life? Is it possible to balance work and family? “PEEP” brings out these kinds of questions, which is remarkable for a work of Japanese photography.

“As an artist, she has a number individual domestic exhibitions every year. At the time (she currently lives alone), she was living in her parent’s house. I thought she always seemed to have an enjoyable life there (the children in the picture are her younger sister’s children).

Her hobby is pachinko, and when she goes to a pachinko parlor she

seems to be there the whole day, from dawn until dusk. A painter who is surrounded by family and has pachinko as a hobby – I think this unexpected combination of things in her life is interesting.”

Certain “types” of people appear that might be familiar to a Japanese audience appear in these photos, but they often show these roles in a complex light. Take the magazine editor, a neat-looking young professional by day, who turns out to be a record-playing, whiskey-sipping Lothario by night. Having seen this come-hither pose, his little smirk in front of the mountains of paper which have built up at his desk takes on a different meaning. The artist’s pachinko habit is surprising in that pachinko is associated with old men, or the lower class in general. She can also afford a devious smile, but that’s not true of the deai site worker, who looks unable to hide his glumness in all three of his portraits. Some people are able to make work less painful—a surfboard maker seems to have struck the best balance—but others seem unable to deal with this tension.

Takiguchi is working in a documentary tradition going back to August Sander, whose portraits still provoke questions about the lives of the people he photographed. Only a historian would look at this work and wonder about Sander’s own life! Because Takiguchi takes a similarly uninterested stance with respect to himself, his work reflects back the lives of his subjects with maybe even more power than he intended—the work well surpasses his concept. (…and how’s that for a change?) Takiguchi has shot around 40 people so far, and he’s hoping to have 100 people completed by next year, at which point he’ll end the project. When it’s over, “PEEP” could very well come to be viewed as a seminal work of Japanese photography for the early millennium.

More images from this series can be seen on Koji Takiguchi’s website.

Captions written by Koji Takiguchi, translated by Adam Bronson.

*Yeah, I do think this is something particularly true of Japan. If you walk down the street and see that someone is dressed a certain way, you might be able to draw one conclusion about them (they like visual-kei, they’re a construction worker, they work in an office, they’re a host, they’re a student) but not much more than that. Many people wear uniforms in Japan, and not just school or company-issued ones; fashion functions in a similar way. Clothes can function like a mask, which makes it easier to preserve one’s private life—which is why it’s so interesting to see two other sides of someone in “PEEP.”

**Philip Lorca-DiCorcia’s “Heads“ series functions, and succeeds, in the exact opposite way.

***I want to suggest that this happens more frequently, and with more finality (especially in the case of work, which is totally incontestable) than in other countries.

Tags (1)

Koji Takiguchi