About a year ago, I wrote some small articles about Japanese photographers for a free paper that was published by IMA Magazine and distributed at Paris Photo, “Japanese Art Photographers 108.” (When the paper was re-printed for the 2013 Paris Photo Los Angeles, it was re-named “Japanese Art Photographers 107” to account for the passing of Shomei Tomatsu.) The goal of this paper was to broadly introduce Japanese photographers to a Western audience. The selection of photographers in this post, and the order in which they appear, are more or less arbitrary. For the most part, I was responsible for the younger photographers of the group, but there were a number of exceptions. The texts appear in the order that I wrote them, so feel free to read whatever you want into that.

Naoya Hatakeyama (b. 1958)

© Naoya Hatakeyama

Hatakeyama’s approach to photography is both technical and thoughtful. The relationship between humans and nature is central to his work, with subjects ranging from Tokyo’s underground tunnels to hills of coal waste in France. His first major project (“Lime Works,” 1996) was a study of lime quarries throughout Japan, and even these early photographs show the meticulous attention to detail which has been carried through the rest of his work. Still, he is no mere technician; he has also published a book of his thoughts on photography. After the 3/11 tsunami wiped out his hometown, he produced a series of photographs which stand as the most impressive photos of the tsunami’s aftermath: despite his personal connection to the disaster, he was infinitely more careful than other photographers who traveled to the affected region. This body of work should only cement Hatakeyama’s place as one of the most cerebral Japanese photographers working today.

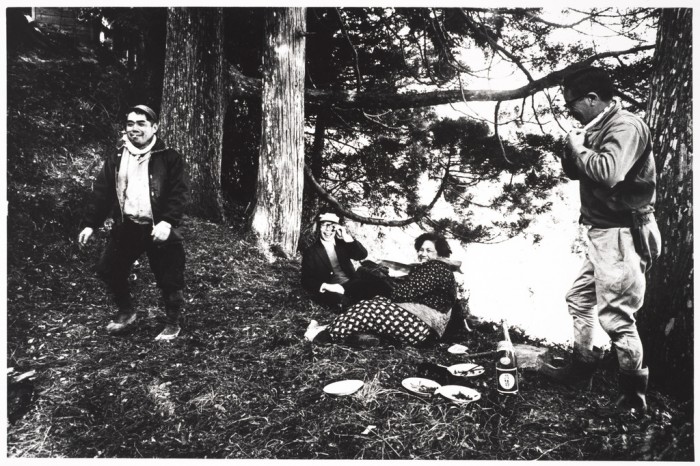

Mao Ishikawa (b. 1953)

© Mao Ishikawa

Born in Okinawa, Ishikawa has taken up themes relating to her native islands and in particular to the issues surrounding the American military bases which remain a major presence there. Her desire to tackle these issues and support Okinawan causes led her to take up photography, and she started working at a bar frequented by American servicemen to create her first project, “Hot Days in Camp Hansen” (shot 1975-77). Later, she traveled to Philadelphia to visit one of these customers, spending two months there to experience his life at home. Her intimate photographs of this time (“Life in Philly,” shot 1986) show not only the full range of her subjects’ emotions, but also Ishikawa’s own willingness to become involved in the lives of the people that she photographs. She has continued to publish books and hold regular exhibitions, while her international profile has been rising. Still, her more recent success abroad is only coming after decades of hard (and largely unnoticed) work.

Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940)

© Nobuyoshi Araki

For Araki, life is photography, and vice versa. His goal has been to bring his own personal experience as close to the medium as possible, and his work encompasses the entire range of human emotion. “Sentimental Journey Spring Journey” (2012), a touching elegy for his deceased cat, is an excellent example of his emotionally unrestrained way of photographing. It’s more than just a photo album; Araki’s connection with this animal comes through so clearly that the images take on a universal, almost cosmic significance. Of course, Araki has also made a name for himself as one of the leading photographers of eros, and nudes are an important part of his work. However, the range of his work has perhaps not yet been fully appreciated outside of Japan. He’s highly profilic: a recent exhibition tried to feature the more than 450 photobooks he’d published to date, but more have already come out. Araki is the face of Japanese photography around the world, and he’s already influenced countless photographers, both in and out of Japan.

Takuma Nakahira (b. 1938)

© Takuma Nakahira

One of the most radical photographers Japan has produced. Nakahira is best known for his work in the late 1960s, during which time he helped start the influential “Provoke” magazine. His 1970 masterpiece, “For a Language to Come,” is a dizzying blend of found urban signage, blurred light and brutal composition, all rendered in a rough black and white aesthetic. At this time, he was also working as an extremely productive and insightful critic, writing hundreds of texts which are still relatively unread even in Japan. However, in 1977 Nakahira suffered an illness which left him unable to write, and almost entirely wiped out his short term memory. Despite this, he has recovered to photograph again, switching from black and white to color. A book of this color work, “Documentary,” was published in 2011.

Haruto Hoshi (b. 1970)

© Haruto Hoshi

Japan has produced its fair share of hard-bitten street photographers, and Haruto Hoshi is the most recent heir to this tradition. Continuing in the vein of Seiji Kurata, Hoshi combines a handheld, flashed look with seedy neighborhoods of Japan, where he himself is no tourist. He’s originally from Yokohama, so this city in particular is well-represented in his work, but he also shoots regularly in Osaka and nearby Tokyo. He started out shooting black and white, and published a book (“Luminance of Streets”) from this work. In recent years, he’s switched to color, and has been holding shows at Tokyo’s Third District Gallery at a fevered pitch–six alone in 2012. Hoshi only shows photographs of people, and although you get the impression that he could get as close as he wants, his wide composition allows the flash to reveal not just his subjects, but their environment as well.

Daisuke Yokota (b. 1983)

© Daisuke Yokota

Yokota’s photographs might look like classic Daido Moriyama images, but he has arrived at his style and method through entirely organic means. He claims director David Lynch and musician Aphex Twin as influences, due to the way they distort sensory information in their respective works. Yokota is attempting to introduce ideas of fade, reverb and echo to photography, and this is what’s led him to his unique approach. To create “Back Yard,” he used a painstaking method in which he printed out his photographs and re-photographed them up to 10 times. Through an intentionally careless developing technique, he introduced new distortions into the image each time that the film was processed. Along with this process of re-photography, he has also used modified versions of the same image in different projects. Yokota recently joined the photographic group AM Projects, which features a number of European photographers and is represented by Doha-based East Wing Projects.

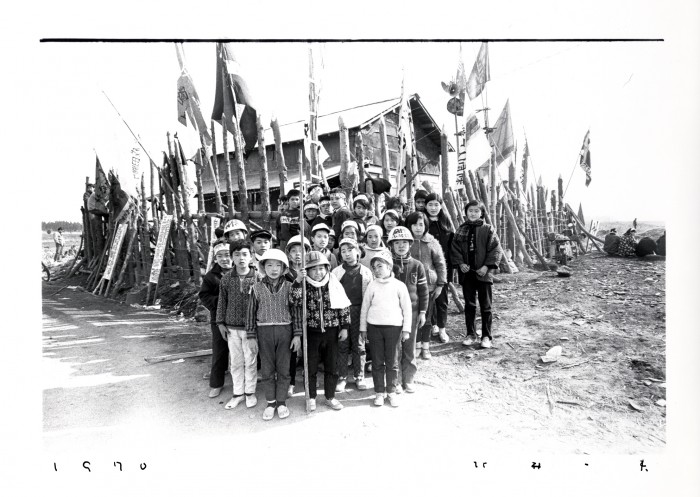

Kazuo Kitai (b. 1944)

© Kazuo Kitai

Kitai’s name is most familiar for his work in the late 1960s, in and around the student protest movements of the time. His early books “Barricade” and “Resistance” reflected the energy of this tumultuous period, while he later spent a significant amount of time in Sanrizuka, site of significant protests against the construction of Narita Airport. His photographs at Sanrizuka were quieter, showing the lives of the peasants on top of whose land the airport would eventually be built. After the end of the student movement, Kitai moved on to shoot similarly rural areas of Japan, perhaps with a premonition that their existence was also threatened on some level. He sent monthly dispatches of this work to Asahi Camera between 1974 and 1977, and it was eventually published as “Mura-e.” Kitai has continued to shoot up until the present day, publishing a book of work on Beijing (“Beijing 90s”) among several others. He still publishes a monthly column in Asahi Camera, and his international reputation has grown with a rise of interest in protest photography. “Barricade” was published in America in 2012.

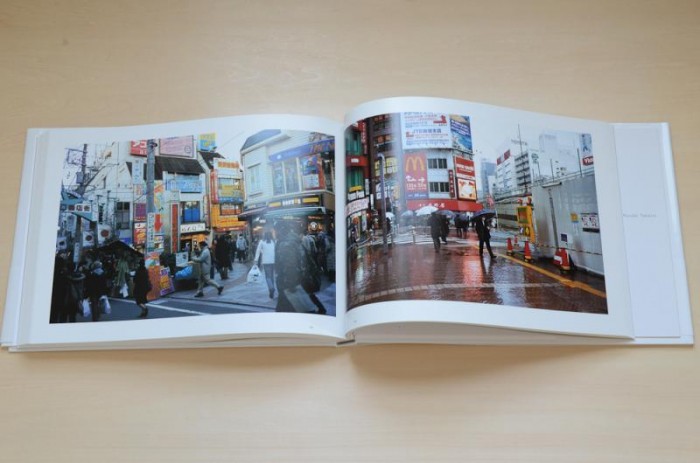

Koji Onaka (b. 1960)

© Koji Onaka

An heir to the Shinjuku tradition of photography as received from Daido Moriyama, Onaka has gone on to develop his own expressive style of snapshots. He started out shooting in black and white, but his color photographs are quite stunning, not just for the exquisite quality of their printing but also their composition. 2001’s “Tokyo Candy Box” is an excellent example of Onaka’s work. It’s a near-comprehensive look at a city in constant change, represented in brilliant hues of orange. Later books like “Grasshopper” (2006) and “Dragonfly” (2007) have shown a quieter side of Japan’s countryside, but with a similarly keen eye for color and form. He’s developed a following outside of Japan. Onaka has run his own artist space in Tokyo, Gallery Kaido, which supports younger photographers. He also recently launched his own publishing label, Matatabi.

Motoyuki Daifu (b. 1985)

© Motoyuki Daifu

Daifu could be seen as a successor to the wave of snapshooters that appeared in the mid-90s, led by HIROMIX. He shoots color photographs in a similarly unrestrained, flash-heavy way, while one of his major works, “Lovesody,” is a diaristic look at a summer fling. Still, even though Daifu is using the same style as these earlier snapshooters, his focus is somewhat different. Where these early works took an intentionally fast-and-loose approach to editing, Daifu has so far only shown well-defined subject matter. His best-developed series, “Family,” is a sometimes humorous, sometimes intense look at the small apartment he with his parents and siblings. Daifu has already published two books in America, “Lovesody” with Little Big Man and “Family” with Dashwood Books. He held a New York City exhibition of “Lovesody” in 2011.

Ryudai Takano (b. 1963)

Takano’s work is carefully balanced between sensitive observation and provocation. While his photographs never hit the viewer over the head with a message, they do often have a slightly subversive edge. Takano’s early work was primarily concerned with sexuality: he won the Ihee Kimura Photography Award for his book “In My Room” (2005), which shows men in various states of undress and arousal. Still, his carefully-written captions and evident technical skill made it clear that he was not simply trying to shock his audience. A more recent book, “Kasubaba” (2011), is an expansive series in which Takano set out to document the ugliest places in Japan. The photographs do not show landfills, but rather entirely normal-looking streetcorners. Again, Takano is pushing the viewer to reconsider their assumptions in a subtle way. He continues to exhibit and publish regularly.

Kayo Ume (b. 1981)

© Kayo Ume

Young female photographers first emerged in Japan in the mid-1990’s. Led by HIROMIX and Yurie Nagashima, among others, these photographers used the directness of the snapshot as a form of personal expression. Kayo Ume, however, appeared in the 2000’s, showing the humorous possibilities of this technique. Her first book (“Ume-me,” 2006) is a collection of snapshots showing absurd moments in the city: a pigeon in a grocery store, a businessman taking a nap on the floor of a train, a young girl making a face at the camera. Far from taking a cool perspective on these situations, it’s clear that Ume is laughing right along with the viewer. “Ume-me” was a runaway hit, and Ume’s later books have shown the antics of young boys (“Danshi,” 2007) as well as her own grandfather (“Jiichansama,” 2008). She is affiliated with the Japanese art collective Hajimeten.

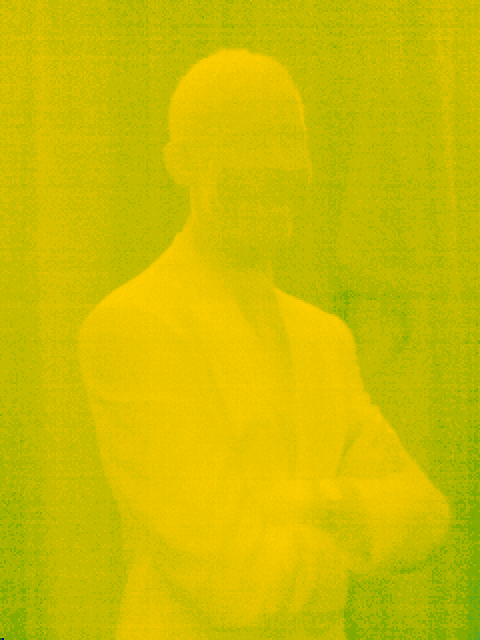

Kenji Hirasawa (b. 1982)

© Kenji Hirasawa

Since 2008, Hirasawa has been based in London, after deciding that it was the most suitable place to develop as a photographer. His 2011 publication, “Celebrity,” has garnered positive attention in Europe. This work was shot with a heat-sensitive camera which represents hot and cold areas of the frame through colors. Aimed at the figures on display in Madame Tussauds, the resulting work renders the famous waxen figures in a vacant greenish blue, while the spectators around these bodies are a more vibrant red. In this way, the work comments on the way that people interact with celebrities in contemporary culture. Hirasawa has continued to use this thermal camera, capturing a different spectrum of what we might call “photography.”

Daido Moriyama (b. 1938)

© Daido Moriyama

Moriyama is known around the world for his out-of-focus, blurry and grainy black-and-white photographs. He emerged in the 1960’s, eventually joining the influential Provoke magazine starting from its second issue in 1968. Moriyama’s 1972 book “A Hunter” represents the now-famous style of this period well. However, there is more to his images than just this harsh aesthetic. Moriyama takes a highly material approach to photography: he re-presents phenomena as photographs, almost using a strategy of appropriation. This is why a seemingly insignificant object like a hat could end up as the cover of one of his well-known books, “Light and Shadow” (1982). A 1999 solo exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art helped to introduce his work to foreign audiences, while London’s Tate Modern is currently holding a large-scale exhibition of his photographs alongside William Klein’s. Moriyama’s recent book “Color” shows that even today, he continues to produce challenging work.

HIROMIX (b. 1976)

© HIROMIX

HIROMIX is a pioneer for female photographers in Japan. She came to prominence after winning the 1995 Canon New Cosmos of Photography competition as a teenager, where her work was championed by Nobuyoshi Araki. Up until this point, photography had largely been the province of men, but HIROMIX’s debut caused a sensation: her freewheeling, self-portrait heavy, snapshot-based style inspired no small number of young women to pick up a camera themselves. Her first book, “Girls Blue,” was published in 1996, and a self-titled book with German publisher Steidl followed in 1998. The Steidl book is an excellent introduction to her work from this period, and shows the casual style which was to influence a generation of photographers to follow. In recent years, HIROMIX herself has come full circle, to serve as a judge for the Canon New Cosmos of Photography.

Masafumi Sanai (b. 1968)

© Masafumi Sanai

Sanai emerged in the 1990s, and has since established himself as a significant contemporary photographer. One of his early books is called “I Don’t Know,” and this title seems indicative of his enigmatic style, which seems to be driven more by aesthetics than the desire to communicate any one thing in particular. Sanai’s photographs are generally quite empty, requiring the viewer to find their own meaning. Still, he has his favorite subjects: suburbs of Tokyo, food and cars. (An early book has the memorable title of “My Ride,” with this roughness fully intended!) He continues to produce work at an impressive rate, and has started a publication series with the noted Tokyo design studio Match and Company.

Hiromi Tsuchida (b. 1939)

© Hiromi Tsuchida

Tsuchida is an accomplished photographer who works on long-term projects; indeed, he’s now been photographing Hiroshima for almost 40 years. His 1976 book “Zokushin” shows Japan’s small rural communities, which would be replaced with urban crowds during the economic boom of the 1980’s. “Counting Grains of Sand” (1990), another black-and-white series, shows this very transition: it begins with photographs shot at eye level of a few people, and culminates in photographs taken at the time of the 1989 Heisei Accession, where teeming crowds literally fill the frame. “New Counting Grains of Sand” (2005) picks up from this point. Although these color photographs of crowds are shot from a high perspective, Tsuchida does not seem to be looking down on his subjects: he has inserted a small likeness of himself into each image. He continues to release new work: in 2011, he published a long-term project on Berlin, showing the city before and after the wall.

Lieko Shiga (b. 1980)

© Lieko Shiga

In her photographs, Shiga creates a dreamy, almost phantasmagoric world, but she doesn’t use Photoshop to achieve this strong effect. Instead, she has developed a unique method of working with her subjects to create the situations that become her work. She has said, “the scenarios I create for my work are a means to instigate moments of unpredictability.” Her book “Canary” (2008), which won the Ihee Kimura Photography Award, shows how these interactions can produce compelling results. Since late 2008, Shiga has lived in Natori City, Miyagi Prefecture, where she has served as the town’s official photographer. Work produced in Tohoku is currently the subject of a solo exhibit (“Rasen Kaigan”) at Sendai’s Mediatheque, and a book is forthcoming. Her work has received an excellent reception both at home and abroad; in 2009 she won ICP’s Young Photographer Infinity Award, while in 2012 she won the Higashikawa New Photographer Award.

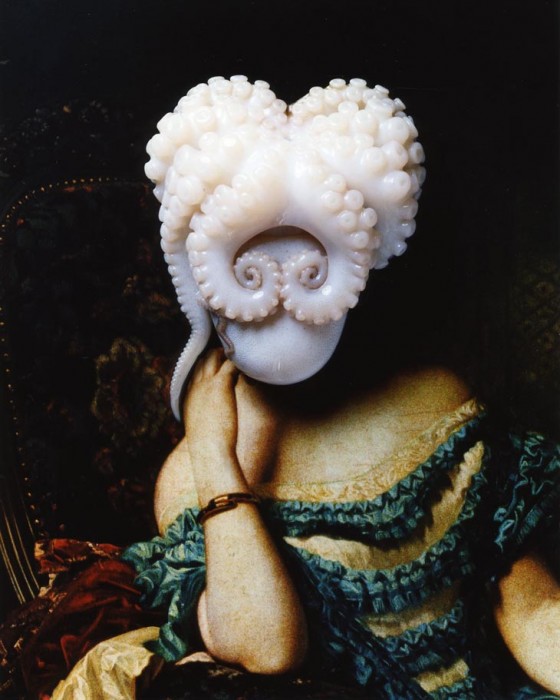

Yumiko Utsu (b. 1978)

© Yumiko Utsu

Utsu works with photography in an extremely playful way. Starting with found images, she then combines them with food, or other objects, to create unexpected effects. Through this technique, an octopus replaces the head of a woman sitting for a portrait, gourds mimic birds sitting on a branch, and a giant scorpion blocks traffic on a highway. Utsu has a particular fondness for using fish and other sea creatures, which lends her work a certain grotesque quality. Her compositions are generally quite colorful, which makes it seem that they’re not meant to be appreciated in an overly serious way. Because of her approach, Utsu has drawn comparisons to Surrealist art. Her works have been collected in a book, “Out of Ark” 2009). In 2012, she participated in a group show at London’s Saatchi Gallery.

Taisuke Koyama (b. 1978)

© Taisuke Koyama

Koyama often works with everyday phenomena, but he presents them in extraordinary ways. In a signature series, “entropix,” he photographs the details of surfaces in Tokyo in such a a way that they come to resemble abstract compositions. However, he is not just attempting to uncover some hidden beauty in these surfaces. Instead, he views this work as a kind of microbiological exploration, as if these minute phenomena could contribute to a broader understanding of the city. To create “Melting Rainbows” (2010), Koyama left prints from a different series out on his balcony, and re-photographed them as the surface changed. This experimental usage of the medium makes Koyama a truly “contemporary” photographer. “entropix” was published as a book in 2008, and his work was recently selected by English curator Charlotte Cotton to appear in the 2012 Daegu Photo Bienniale.

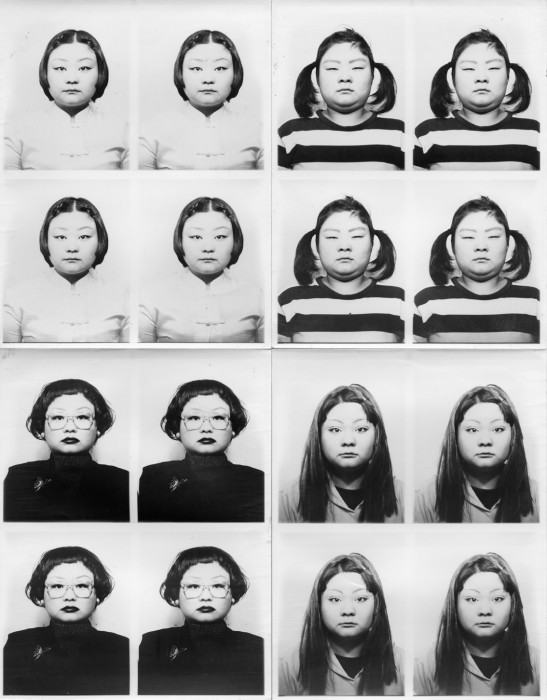

Tomoko Sawada (b. 1977)

© Tomoko Sawada

Sawada uses photography to explore the relationship between one’s inner life and outer image. Sawada herself is often the subject of her photographs, making herself up to look like a certain well-known “type” of Japanese woman: an office worker, “gyaru” or hostess, among others. For “School Days,” one of Sawada’s best-known works, she produced a series of images which mimic the typical class photo of an all-girls school. Everything seems as normal, except that every student–and the teacher as well–is, in fact, Sawada. Although many critics view Sawada’s work as a comment on popular images of women in Japanese society, others see it as a more personal exploration of the self. Sawada is based in New York City, and has exhibited extensively outside of Japan. In 2004 she received ICP’s Young Photographer Infinity Award.

Tags (20)

Daido Moriyama, Daisuke Yokota, Haruto Hoshi, Hiromi Tsuchida, HIROMIX, Kayo Ume, Kazuo Kitai, Kenji Hirasawa, Koji Onaka, Lieko Shiga, Mao Ishikawa, Masafumi Sanai, Motoyuki Daifu, Naoya Hatakeyama, Nobuyoshi Araki, Ryudai Takano, Taisuke Koyama, Takuma Nakahira, Tomoko Sawada, Yumiko Utsu